It's been a minute

Here's where to find me now

It’s been a minute, as the kids say. I haven’t written on this Substack for well over a year as I took up a new role and focused my writing over there.

But there’s been a steady uptick of new subscribers to this publication, so I thought I’d let you know where you can find my work now, if you’re interested.

These days I write about issues connected with freedom of conscience, religion and belief as the CEO of Ethos. Briefly, Ethos is a charity that helps people live out their most important commitments. We work with a network of lawyers to support clients, offer information and education to the general public, and provide resources for lawyers.

Most of what I write is connected with the kinds of issues people bring to us—often, and obviously, the most sensitive issues in our society—and relevant big picture questions like what it means to be human and the obligations we owe to our neighbours (just the easy stuff). There’s often a legal element to this work, but it’s written for a general audience—the kind that might have found this Substack interesting when it was operational.

Ethos publishes a monthly email newsletter, and if you want to follow along you’re welcome to sign up here. Below is a taste of what you’d get if you signed up.

Should uniformed Police take part in Rainbow Pride events? A UK court says no

Jump onto the New Zealand Police’s Instagram page and scroll to February 2024. The official account announces that Police were “proud to march in the Auckland Rainbow Pride Parade” and to “show our support for the rainbow community.” Uniformed officers, one holding the Progress Pride flag emblazoned with a Police logo, pose with two young girls wearing Progress Pride t-shirts.

What’s the big deal, you might be wondering? The short answer is that the Police are supposed to be impartial, but a new court decision from the UK demonstrates that participating in Pride marches, or any other protest, rally or campaign, might undermine this duty.

New Zealand Police need to consider this carefully. Here, as in the UK, impartiality is a core principle of policing because it’s crucial for public trust and social cohesion. As our Police say themselves, trust is earned by treating everyone fairly, which means everyone gets “impartial and just treatment ... without preference or discrimination.” This isn’t just a nice-to-have, it’s a legal duty imposed by the Policing Act and reinforced by the oath that new officers swear, to serve “without favour or affection”.

Whether marching in parades, fitting out patrol cars in Pride colours, wearing Police t-shirts with the colours of the transgender flag, or displaying the Progress Pride flag on police stations, our Police are also creating the impression that they are taking sides on a subject that is rather obviously a subject of passionate and legitimate debate. Police should reconsider the message they’re sending by associating themselves with these potent symbols.

This article was first published by LawNews on 25 September 2025.

Supporting pro-life advocates threatened with arrest

This is an example of a case study—a brief summary of a case we assisted in, told with our client’s permission.

On 21 February 2025, Grace for Life were in the Hamilton CBD when they were approached by a senior Police officer. Their team were displaying a sign that featured an image of an unborn baby at 20 weeks’ gestation, and encouraging pregnant women to “choose life”.

The officer asked them to put away the sign away, saying Police had received complaints about the sign and “Any person who complains about anything to us, if they feel that is offensive, that is an offence.” The officer also stated a personal view that the sign was “offensive” and told the team that the Summary Offences Act 1981 “basically says if anyone feels offended by something, they can make a complaint” and police would arrest the offending party as a result.

The Grace for Life members put the sign away because they didn’t want to be arrested, even though they didn’t think they were doing anything wrong.

That’s when Ethos got involved.

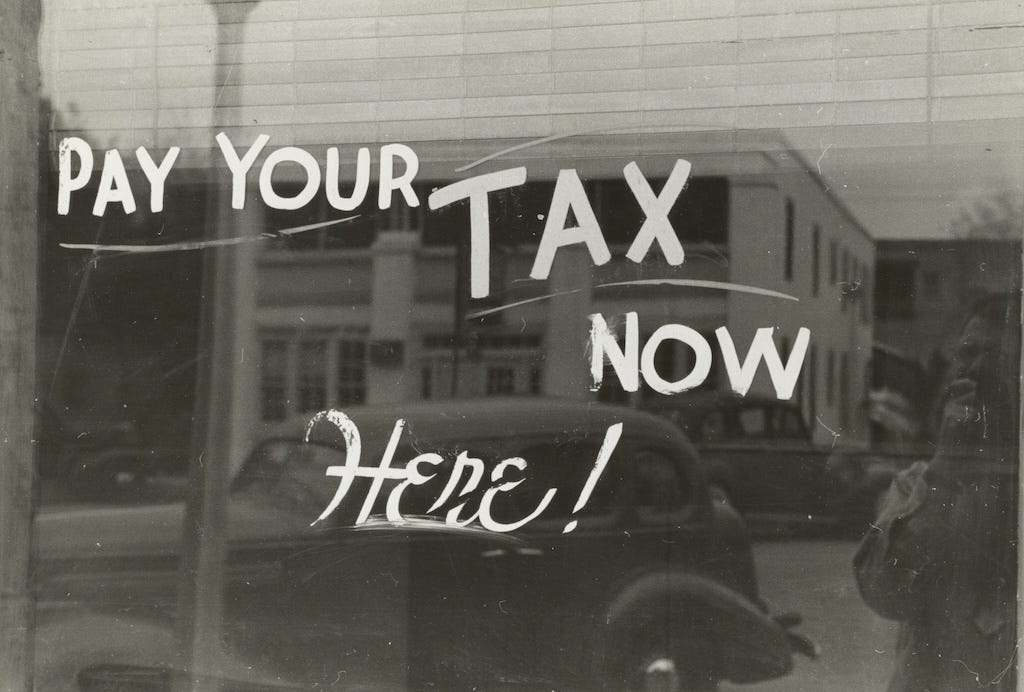

Religion doesn’t deserve a sin tax

A “sin tax” is meant to penalise and prevent undesired behaviour, like alcohol and tobacco taxes. So it’s ironic that some people have used the current debate about charities and business income to advocate for taxing religion.

There’s been plenty of discussion about whether charities that also run businesses should pay tax on their commercial income, but this issue is different. The New Zealand Association of Rationalists and Humanists recently argued that “advancement of religion” shouldn’t be treated as a charitable purpose any more, meaning religious organisations would lose associated tax advantages. This is doubly ironic, for reasons we’ll get to later.

For now, let’s note this just looks like plain opposition to religion. It also reflects a common failure to understand why, as a society, we might value religion.

Simply put, religion is a personal and social good and we should treat it as such. This is a large topic, but here are four brief reasons to agree.

This article was first published by The Post, the Waikato Times, and The Press on 29 April 2025.

What does good faith disagreement look like?

Recently I had an op-ed in Stuff publications that argued we should embrace the good in disagreement—that passionate disagreement isn’t a bad thing, or merely a necessary price we pay for democracy, but a way that we love our neighbours. Not every disagreement is loving, but I argued that “when we’re so used to seeing good-faith dissenters dismissed as haters and bigots, we need to recalibrate how we understand disagreement.”

Of course, that leads to a reasonable question—what does good faith disagreement look like, and how can we do it?

To answer that question, I’m going to borrow from the Inkling, an initiative that was created “to help nurture positive public conversations in Aotearoa New Zealand.” The Inkling hosted conversations about important issues and it established rules of engagement to support these gatherings. With their permission, I’ve produced a modified version of the rules which incorporates some of what I described in my Stuff article. I think these norms offer the prospect of constructive and good-faith debate even about the sensitive issues that are most hotly contested.

Click here to read our 9 rules for good faith disagreement

BNZ v The Christian Church Community Trust (Gloriavale)

This is an example of a case note—a summary of a relevant court decision.

Gloriavale is a controversial and reclusive Christian community which also operates a number of commercial enterprises. In 2022, three ex-members obtained a declaration from the Employment Court that they were legally employees when they worked in those enterprises as children. The judge found that “the ready access to child labour (children of adult residents) constitutes a significant factor in the success of the Gloriavale business model”, and that children were if necessary coerced to work in conditions that were “often dangerous [and] required physical exertion over extended periods of time”. Consequences for non-compliance with the direction of Gloriavale’s leadership included “physical and psychological punishment”.

Gloriavale has banked with BNZ since 1999, but after the Employment Court’s decision BNZ decided to terminate all the accounts held by Gloriavale and its entities. BNZ relied on its standard terms and conditions, which said that it could close a customer’s account “for any reason,” and on its internal human rights policy which committed it to avoid complicity in human rights abuses including “forced labour, or child exploitation”. Gloriavale contested BNZ’s interpretation of events and of the terms and conditions, and obtained an interim injunction in the High Court that prevented BNZ from closing the accounts pending a full hearing of the dispute. This was significant as Gloriavale had been unable to find another bank willing to provide services.

BNZ appealed against the interim injunction, and won.

Euthanasia review reveals a flawed law and proposals to erode conscience rights

This is an example of our engagement with law reform proposals, in this case the Ministry of Health’s review of the End of Life Choice Act.

Recently the Ministry of Health released its review of the End of Life Choice Act. It’s quite a revealing read. Perhaps the most striking insight is how badly written the law is, but the review also illustrates the ideology that animates the Ministry, which underlies its proposals to erode conscience rights. The review also indicates that we can expect the number of New Zealanders euthanised to keep growing, and that we can’t expect ACT’s current member’s bill to fix anything. In fact, their proposed expansion of the law is likely to exacerbate the problems the Ministry has identified and the pressure on doctors who don’t want to participate in this regime.

Let’s start with the good news: the review shows that the Act is poorly thought-out and badly written. It doesn’t use those words but it collects multiple examples that lead to that conclusion, and it’s refreshing that the Ministry has been clear about these flaws. Here are some of the key issues they identified.

In defence of our right to say what we believe

Everyone has some controversial beliefs.

But how comfortable are we telling people about them? For many of us, the answer is: not very.

We commissioned new research asking New Zealanders whether they thought society should have more tolerance for people expressing differing beliefs even if they are unpopular or about sensitive issues like sex and gender identity, the Treaty of Waitangi, hate speech, or religion. The majority — 59% — agreed that we need to be more tolerant than we are; just 11% disagreed.

There’s a growing sense that society’s becoming more censorious, more willing to sanction people whose beliefs aren’t consistent with the prevailing attitude or popular belief. There’s an obvious concern about suffering social stigma, or worse, if you hold the “wrong” beliefs. Overseas, banks have been accused of closing customers’ accounts because of their political views, like campaigning for Brexit or participating in protests, or their views on issues like gender and sexuality.

Living out our deepest convictions is a fundamental human right, recognised in law. The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act says that everyone has the right to “freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and belief”, and the right to “manifest that person’s religion or belief” through, for example, practice and teaching.

Sometimes these beliefs lurk just below the surface of everyday activity and only come into view when there’s some kind of crisis. Beliefs like these don’t usually feature in public debate but they’re there nonetheless, shaping our leaders’ decisions and our nation’s future.

This article was first published by The Post on 13 March 2024.

Thanks for reading this far! If you’re interested in more like this, you can subscribe for future Ethos newsletters here.